The data tells a clear story. Despite frameworks, funding, and political will, New Zealand’s public sector AI adoption is stuck in a cycle of pilots, caution, and quietly used personal accounts. Here’s what’s actually happening — and what needs to change.

There’s a version of the New Zealand government AI story that sounds genuinely impressive. Seventy agencies surveyed. A national AI strategy launched. A Public Service AI Framework in place. $213 million allocated for tuition and training. $70 million committed to the NZ Institute for Advanced Technology. Masterclasses for leaders. Foundational courses for public servants.

Read the press releases and you’d think the New Zealand public sector was well on its way to becoming an AI-powered operation.

Then you look at what’s actually happening on the ground.

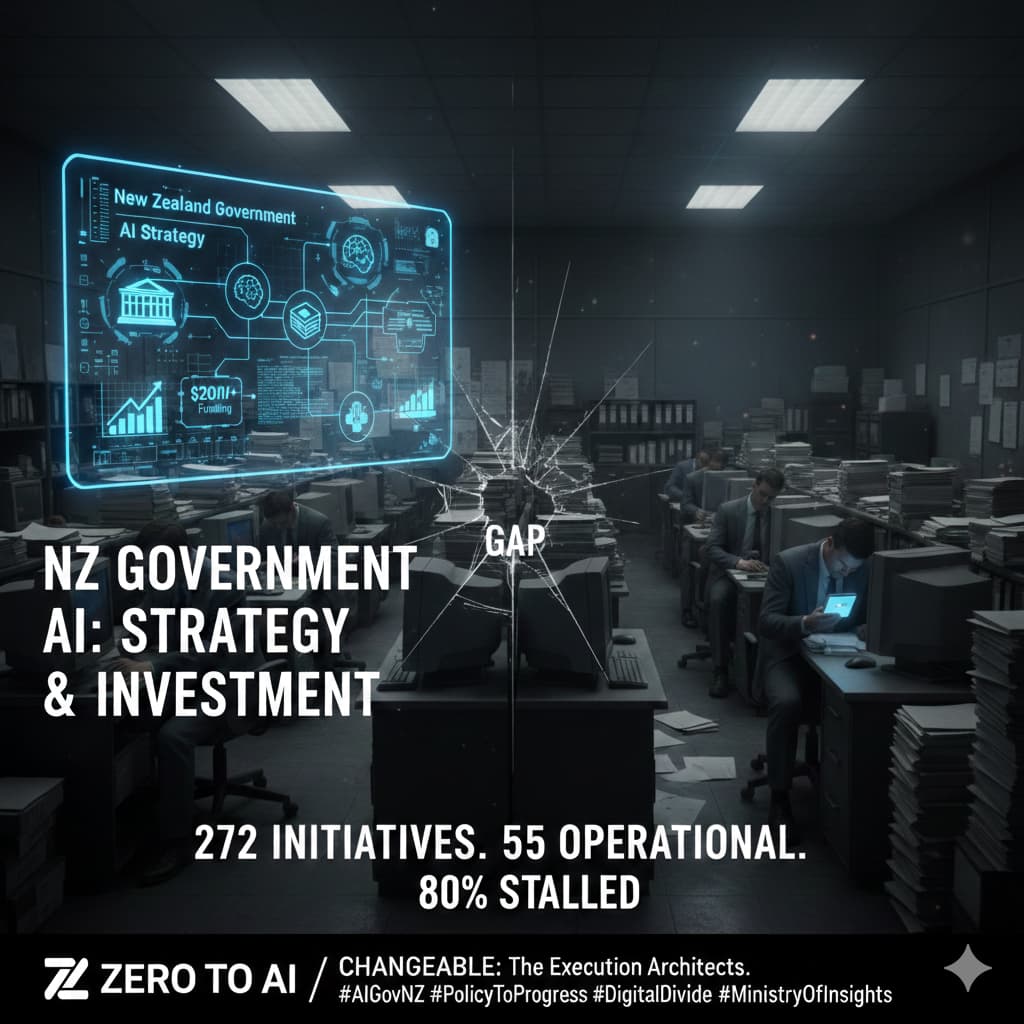

Of 272 AI use cases reported across government in 2025, just 55 are operational. That means 80% of identified AI projects are still sitting in planning, trialling, or “ideas” phases. The ones that have made it to production are overwhelmingly low-risk: summarising feedback, automating meeting notes, basic search. Not core service delivery. Not decision support. Not the kind of work that transforms how government operates.

This isn’t a technology problem. It’s an institutional one. And until someone names it clearly, the cycle of expensive strategy followed by cautious inaction will continue.

The Numbers Behind the Narrative

The GCDO’s 2025 cross-agency survey is the most comprehensive picture we have of AI in New Zealand government. The headline numbers look like progress — 272 use cases, up from 108 the previous year. Seventy agencies participating, nearly double 2024.

But the detail underneath tells a different story.

Fifty-five operational use cases across 70 agencies means most agencies have zero or one AI project actually running in production. The majority of reported activity sits in categories like “idea,” “trial,” or “planning” — categories that generate survey responses but not outcomes.

The use cases that are operational cluster around safe, low-stakes applications. Document summarisation. Meeting transcription. Internal search. These are useful, but they’re the AI equivalent of using a smartphone only for phone calls. The capability exists to do vastly more, and the gap between what’s possible and what’s permitted is enormous.

Compare this with the private sector. Across New Zealand businesses, AI adoption is running at 82-87%. Not pilots — actual operational use. The government’s own strategy acknowledges this gap exists. It just hasn’t figured out how to close it.

The Defence Case Study: Policy as Paralysis

The Ministry of Defence and New Zealand Defence Force illustrate the problem at its most extreme.

As of mid-2025, the NZDF confirmed they are not using AI operationally or in production. Staff are prohibited from using AI-generated information for work without explicit approval from a Deputy Secretary. Their only autonomous system — the Phalanx close-in weapons system — predates modern AI by decades.

Now, there are legitimate reasons for caution in a defence context. Security classification, operational sensitivity, and the consequences of AI errors in a military environment are real and serious.

But the blanket prohibition approach creates its own risks. It means the organisation builds zero internal capability. It means when AI eventually becomes unavoidable (and it will), the institutional knowledge to deploy it safely doesn’t exist. And it means the gap between New Zealand’s defence capability and those of allies who are actively integrating AI widens every year.

The MoD approach isn’t strategy. It’s deferral dressed up as caution.

The International Context: Last to Move, Slow to Follow

New Zealand was the last OECD country to release a national AI strategy. That happened in July 2025, six years after Singapore published theirs and well after comparable small economies had established formal frameworks.

In the Oxford Insights Government AI Readiness Index, New Zealand sits 40th globally. Behind Singapore (3rd), behind Australia, behind most of the economies we’d normally consider peers.

The government’s own strategy acknowledges this. It positions New Zealand as an “adopter nation” — explicitly choosing to implement proven AI solutions rather than develop new ones. That’s a sensible strategic choice. But adopting implies actually adopting, not just writing documents about intending to adopt.

The strategy’s language gives the game away. It talks about “creating an environment” where businesses can invest, “encouraging” adoption, and “removing barriers.” These are the verbs of facilitation, not action. They describe a government that wants to be seen as supportive without taking on the institutional risk of going first.

The Skills Gap Is Real — But It’s Not the Whole Story

Internal data paints a clear picture of capability challenges. Only around a third of public servants believe they have the skills to use AI appropriately. The Datacom State of AI Index found 43% of non-users cite lack of expertise as their main barrier to adoption. Half of senior leaders across government and large enterprises believe New Zealand is lagging behind other countries on AI.

These are real problems. But the skills gap is also being used as a convenient explanation for something more fundamental: a cultural unwillingness to accept the risk that comes with doing something new.

You don’t need deep AI expertise to use a summarisation tool. You don’t need a data science degree to draft correspondence with AI assistance. The skills required for the low-risk, high-value applications that should be table stakes across government are modest. What’s missing isn’t capability — it’s permission.

The Deputy Secretary approval requirement at Defence is an extreme example, but the pattern repeats in softer forms across the public sector. Risk-averse cultures create approval bottlenecks. Approval bottlenecks create delays. Delays become the status quo. And the status quo gets reframed as “responsible adoption.”

Shadow AI: The Elephant in the Room

While official channels move cautiously, public servants are making their own decisions. Research indicates that roughly 44% of workers have used generative AI tools, with a significant proportion not disclosing this to management. A Fishbowl study found 68% of staff don’t tell their bosses when they use AI.

This is shadow AI — unsanctioned, ungoverned, and invisible to the people responsible for data security and policy compliance. Staff are uploading internal documents to ChatGPT, pasting sensitive information into free-tier AI tools, and using outputs without any quality assurance or audit trail.

The irony is sharp. The same organisations that won’t approve AI pilots because of data security concerns are creating conditions where data leakage is happening anyway, completely outside any governance framework.

Shadow AI isn’t a failure of staff discipline. It’s a failure of institutional leadership. When the official process for using AI is “don’t, unless a Deputy Secretary says you can,” people who need to get work done will find another way. Every time. The productivity advantage is too large to ignore, and the tools are too accessible to block.

The answer isn’t tighter restrictions. It’s providing sanctioned, governed access to AI tools with clear guardrails, so that the usage that’s already happening moves from the shadows into a framework where it can be monitored, improved, and made safe.

The “Sinking Lid” Trap

There’s a revealing pattern in how agencies are thinking about AI’s role. Rather than using AI to expand capability or improve services, many are focused on what’s been described as a “sinking lid” approach — using AI to upskill remaining staff as positions go unfilled, rather than replacing departing workers.

On paper, this sounds pragmatic. In practice, it’s a recipe for stagnation.

It means AI is being positioned as a cost-management tool, not a capability multiplier. It means the ambition is to maintain current service levels with fewer people, not to deliver better outcomes. And it means the conversation about AI is framed defensively — protecting what exists — rather than asking what could be different.

This is the institutional equivalent of using AI to tread water instead of learning to swim.

Government agencies facing budget pressure and staffing constraints have a legitimate need to do more with less. But the “sinking lid” framing caps the ceiling on what AI can achieve before anyone has tested the limits. It turns AI into a headcount management tool when it could be a service transformation engine.

What Would Actual Adoption Look Like?

The gap between where New Zealand government sits and where it could be isn’t a technology gap. The tools exist. The frameworks exist. The funding exists. What’s missing is the institutional willingness to move from strategy to execution at pace.

Actual adoption would mean every agency having at least one AI-assisted process in core service delivery — not just meeting notes, but consenting, case management, policy analysis, or citizen communication. It would mean procurement frameworks that allow agencies to trial AI tools without a twelve-month approval process. It would mean measuring AI adoption by outcomes delivered, not use cases reported.

It would mean accepting that some implementations will fail, that some outputs will be wrong, and that the cost of learning from those failures is vastly lower than the cost of not starting.

And critically, it would mean addressing shadow AI head-on. Not by banning it harder, but by giving every public servant access to a sanctioned, secure AI environment with clear rules about what data can and can’t be used. The tools cost less than a single FTE. The risk of not providing them is already materialising in every agency that thinks it has AI under control.

The Consulting Opportunity — and the Honest Assessment

For organisations like Changeable, this gap between strategy and execution is exactly where the work needs to happen. Not more frameworks. Not more strategies. Practical, on-the-ground support that helps agencies move from their 55th pilot to their first scaled deployment.

That means governance that enables rather than blocks. Change management that builds confidence rather than compliance. AI literacy programmes that start with the actual work people do, not abstract concepts about responsible innovation.

But it also means being honest about what we’re seeing: a public sector that has invested heavily in the appearance of AI readiness while remaining, in practice, cautious to the point of paralysis. The strategy is there. The funding is there. What’s missing is the courage to do it — and the practical support to do it well.

New Zealand’s government doesn’t have an AI strategy problem. It has an AI execution problem. And every month that the 80% of identified projects remain in planning is a month where the gap between what’s possible and what’s permitted gets harder to close.

Steve Wilson is the founder of Changeable and Ministry of Insights, providing AI strategy, governance, and automation consulting for organisations navigating the gap between AI ambition and AI reality.